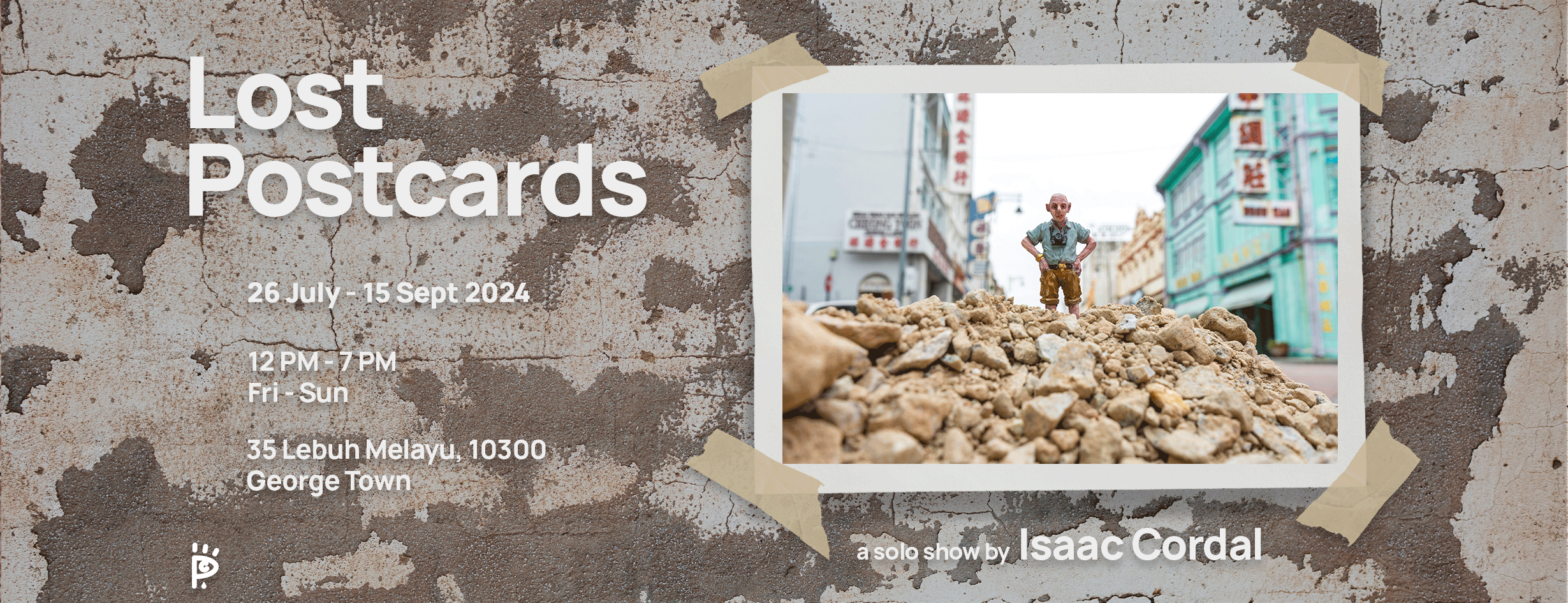

“Sink About It”

Artists: Isaac Cordal x Ernest Zacharevic

Medium: Hand-finished Archival Pigment Print on 310gsm, Hahnemühle 100% α-cellulose German Etching Paper

Size: 30cm x 35cm

Year: 2024

Limited Edition of 30 | Hand-Embellished by the artist- Ernest Zacharevic | Signed by both artists with a Certificate of Authenticity

Artist Isaac Cordal and Ernest Zacharevic team up in this exciting new print “Sink About It”. Featuring Isaac’s signature balding figures in a grey suit, the print is then hand-finished by Ernest. Featuring an array of funny floats, from ducks to a wreath of flowers. Each piece is unique and a mark of both artists creativity. We hope you love them as much as we loved producing the prints.

Using photography and sculptures, Cordal emphasises on the double – edged concept of mass tourism. He suggests that tourists are the most effective army in history, and at some point, we are all part of an immense mass that colonises the world. We change into our vacation clothes, just to be part of the machinery called tourism. We open our suitcases in remote places, look out the window and everything becomes an immense set. We stand in huge lines under the sun to confirm that what we see is real, and corresponds to the image described in travel guides. It fills us with vitality to observe that the passage of time and nature have not yet completely overcome the vestiges of the past, and for a moment, a halo of immortality is captured on our memory cards. The terrifying thing is that these places disappear as we visit them.

Using photography and sculptures, Cordal emphasises on the double – edged concept of mass tourism. He suggests that tourists are the most effective army in history, and at some point, we are all part of an immense mass that colonises the world. We change into our vacation clothes, just to be part of the machinery called tourism. We open our suitcases in remote places, look out the window and everything becomes an immense set. We stand in huge lines under the sun to confirm that what we see is real, and corresponds to the image described in travel guides. It fills us with vitality to observe that the passage of time and nature have not yet completely overcome the vestiges of the past, and for a moment, a halo of immortality is captured on our memory cards. The terrifying thing is that these places disappear as we visit them.

26-10-2023 / 25-02-2024

26-10-2023 / 25-02-2024