“Sobre la incertidumbre y la representación. Javier Tudela”

dos Hay algo platónico en la ‘materialización’ de ideas; en la escenificación de estos ‘dialogos’, el autor negocia con el material, pone a sus cuerpos la tarea de compartir el espacio y los convierte en personajes conversando mientras esperan al espectador para una nueva conversación. En la caverna de Platón, sus habitantes están siempre de espaldas a la luz de la hoguera e imposibilitados para atender al mecanismo de

proyección. Por eso confunden las sombras con el mundo real, son engañados por sus sentidos y asisten a una representación fantasmal, un teatro de sombras, copias desfiguradas que les impiden saber de las cosas reales. Con esta metáfora Platón se sirve de las imágenes para comparar el conocimiento de los sentidos frente a la verdadera sabiduría que proviene de la razón; su caverna es a la naturaleza -allí donde consigue escapar el filósofo y donde aparecen las cosas reales- lo que nuestra naturaleza es al mundo de las ideas.

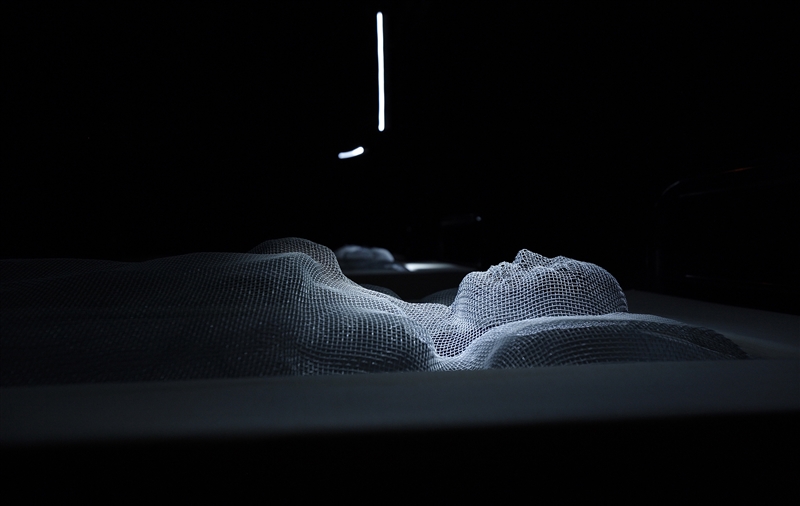

Este mito es, además, un alegato a favor de la responsabilidad pedagógica del filósofo; la tarea del artista también está rodeada de pedagogía y no exenta de valor. Isaac Cordal está preocupado por la escultura y ocupado con el material, contradice a Platón, como ya lo hizo su discípulo Aristóteles; trabaja con los cinco sentidos y también para los sentidos. No existe nada en la mente que no haya cribado antes nuestra experiencia. No existe la obra si no es sentida, si no es para los sentidos. La materia se esfuerza en hacer realidad sus posibilidades inherentes. El alambre, la luz actúan como principios indeterminados carentes de forma pero capaces de acoger toda información. Algo semejante al tejido de metal que vemos en las obras ocurre en los procesos embrionarios cuando se ‘hacen’ las personas. A partir del primer acuerdo fecundo, la intención queda recogida en la información que aportan dos células y se produce el crecimiento y la diferenciación celular. Tan importante es el aporte de material como la diversificación de las tareas a las que se va atendiendo: respirar, moverse, ver, alimentarse, defenderse… la función crea el órgano y el organismo/figura se prepara para sobrevivir, en este caso, entre los seres estéticos, entre otras obras. Y tan importante es la construcción de sus cuerpos como su interacción con el mundo que los hace personas. Se articulan las ‘figuras’ de alambre desde la experiencia del constructor de ‘ocurrencias’ y desde la memoria y el ejercicio del tacto, de la dureza y la flexibilidad de las cosas y del mundo, en una negociación entre lo inteligible y la emoción, entre lo sensible y la física, entre la física y la representación, entre la representación y el gesto. Las figuras crecen desde el vientre al pecho, a la cabeza, recorriendo los estadios de la habilidad del alma platónica –desde el deseo, por la voluntad, hacia la razón- Pero su escultura no pone en duda el interés de la experiencia.

No nos escamotea el fuego/luz con un muro imposible de rodear. Las figuras de Isaac Cordal no abundan en la crítica hacia las cosas representadas en detrimento de las cosas que existen y de sus construcciones ideales porque lo que interesa aquí no es la distancia entre la máquina humana y su representación, lo que se propone no es una burda reconstrucción de la naturaleza. La malla trama otra cosa diferente a la mera imitación. Este demiurgo también sugiere imágenes en otro lugar diferente a los materiales, pero no escamotea la evidencia de su construcción ni del artificio que modifica la apariencia de su puesta en escena.

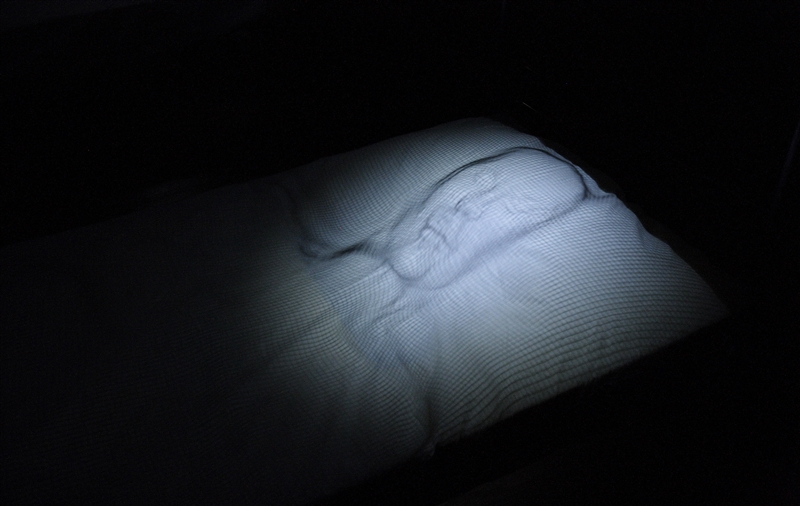

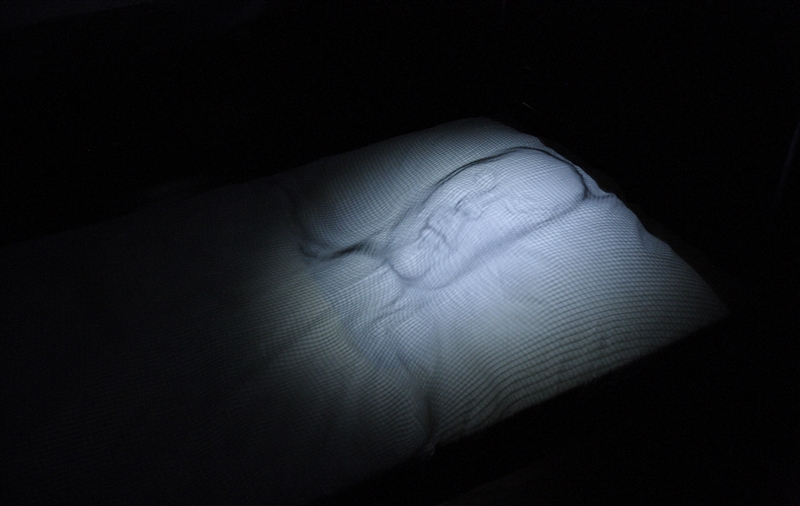

tres Personajes, máscaras y dobles figuras se agrupan en torno a su propia construcción y se separan para subirse por las paredes. Sombras animadas proyectadas desde luces en movimiento. Procesos y puestas en escena dinámicos y complejos. Personajes marcando su territorio construyendo a la vez su posición, su diálogo y su reflejo. La evidencia de los mecanismos, la precariedad con la que se construyen indica que se huye del espectáculo. Tampoco con la ‘animación’ de las figuras y de las máscaras se trata de recrear la atmósfera que los hermanos Lumière consiguieron hace ya más de cien años en París, no parece importar demasiado el artificio. En aquella ocasión, uno de los periodistas que acudió a la presentación de su linterna mágica escribió: “Con este nuevo invento, la muerte dejará de ser total y absoluta; las personas que hemos visto en la pantalla permanecerán con nosotros, vivas y activas, después de su fallecimiento” No es extraño que el cine evocara la función de las máscaras funerarias y la tarea en otro tiempo asignada al arte de sugerir la presencia del poderoso, de la amada, del paisaje, allí donde no estaba. Las máscaras de los actores tenían otra función, estaban hechas per sonare, para hacerse oír, este es el origen latín de la palabra persona. Las máscaras que vemos ahora son coladores de luz, ocultan y reflejan. En el fondo puede que lo que Isaac Cordal -lo que el arte y la vida- intenta es resistir. Resistir en tiempos difíciles –para el arte siempre son tiempos difíciles-. Es un ejercicio de equilibrista sostenerse en el alambre y, además, construir interruptores para burlar a la noche, reconstruir personas. La luz se mueve con el aliento de los motores excéntricos y las imágenes fantasmales cambian, maniobran en el viaje entre su posibilidad y su realidad: la indeterminación que se produce es otra llamada de atención sobre la complejidad del mundo.

Capítulos de “Sobre la incertidumbre y la representación”

Camas de cuerpos ausentes, sombras de personajes, dobles figuras, rostros desfigurados ó máscaras son proyectadas mediante una puesta en escena dinámica y sofisticada pero utilizando materiales precarios para huir de toda pretensión tecnológica. Javier Marin

Two There is something Platonic in the “materialization” of ideas. In the staging of these “dialogues”, the author deals with the material, assigning to it the task of sharing space; he converts the material into conversing characters that wait on the onlooker for a new conversation. In Plato’s cave, the inhabitants are always faced away from the light of the fire, preventing them from paying attention to the projection mechanism. Because of this, they confuse the shadows with the real world; they are deceived by their senses; they attend a phantasmal representation, a theatre of shadows, disfigured copies that hinder them from knowing the real objects. With this metaphor, Plato uses images to compare the knowledge of the senses against the true wisdom that is derived from reason; Plato’s cave is to nature – where the philosopher can manage to escape and where real objects appear, just as our

nature is to the world of ideas.

This myth is also an argument in favour of the pedagogical responsibility of the philosopher. The task of the artist is also enveloped in pedagogy and equal in importance. Isaac Cordal is concerned with sculpture and occupied by material; he contradicts Plato, like his disciple Aristotle did. He works with the five senses and also for them. Nothing exists in the mind that has not been filtered by our experience. A work does not exist if it is not felt, if it is not created for the senses.

The material tries to make its inherent possibilities a reality. The wire and the light act as undetermined beginnings lacking in form but capable of receiving information. The embryonic processes that occur when people “grow” can be seen in the metal tissues present in the works. After the first fertile union, intention is determined from the information contributed by the two cells as growth and cellular differentiation is produced. The contribution of material is just as important as the diversification of the tasks that are carried out: breathing, moving, seeing, feeding, defending oneself, etc. The function creates the organ and the figure or organism

prepares itself to survive, in this case, among aesthetic beings, among other works. And the construction of their bodies is just as important as their interaction with the world that makes them real.

The wire figures are articulated by the experience of the builder, by “accidents”, by the memory and exercise of touch, by the hardness and the flexibility of objects in the world, by a negotiation between the intelligible and emotive, between the sensed and the physical, between physical, representation and gesture. The figures grow from the womb, to the chest, then to the head; they cover the phases of capability of the Platonic soul – from desire, to free will, towards reason.

His sculpture does not, however, place in doubt the interest of experience. The fire and light do not hold us back with a wall that is impossible to scale. The figures of Isaac Cordal are not criticizing objects represented to the detriment of already existing objects or their ideal constructions. What interests us here is not the distance between the human machine and its representation. What is proposed is not a crude reconstruction of nature. The wires plot something different, something other than mere imitation. This demiurge suggests images in a place distinct to their materials; but it does not hold back evidence of its construction nor of the

artifice that modifies the appearance of its staging.

Three Characters, masks and double figures group together around their own construction and then separate to climb the walls. Animated shadows projected from moving lights, complex and dynamic processes and staging. Characters marking their territory, creating their position. Dialogue and reflection at the same time. The evidence of the mechanisms and the precariousness with which they are constructed indicate a fleeing spectacle. Not even with the “animation” of the figures or the masks can the atmosphere that the Lumière brothers achieved over one hundred years ago in Paris be recreated. The artifice does not appear to matter much. On that occasion, one of the journalists that attended their magic torch presentation wrote, “With this new invention, death will no longer be total and absolute; the people that we have seen on the screen will remain with us, alive and active, long after their death.” It is not surprising that cinema would evoke the function of the funeral masks. It also produces the task assigned to art: to suggest the presence of the powerful, of the loved, of the landscape, in a place where it did not exist. The masks of the actors had another purpose; they were made to dream, to allow one to hear; this is the Latin origin of the word person. The masks that we see here are colanders of light; they hide and reflect. Deep down it could be that Isaac Cordal, like art and life, is trying to resist. To resist the difficult times – for art is always difficult times. It is a balancing act: to sustain oneself on the wire, to construct switches in order to evade the night, and to piece together people. The light moves with the wind of the eccentric motors; the phantasmal images change. They maneuver in a journey between their possibility and their reality. The irresolution that is produced is also another reference to the complexity of the world.

Chapters in “On the uncertainty and the representation” Javier Tudela